When Intel’s Kaby Lake CPU arrived at our doorstep in the form of Dell’s XPS 13 laptop, it was wrapped in foreboding. Hardware fans have long been in denial about the inevitable end of Moore’s Law. With Kaby Lake, Intel’s abandoned its relentless “tick-tock” march in favor of a slower “process-architecture-optimize” stroll. Semiconductor doomsday seemed nigh.

Kaby Lake is the first CPU produced under Intel’s new plan. The plan started with a “tock”—a CPU shrink (22nm Haswell to 14nm Broadwell), then a “tick” of efficiency improvement (14nm Broadwell to 14nm Skylake). Intel wasn’t ready to produce another tock yet, though. Instead we got a second tick, an “optimized” 14nm Kaby Lake. The question is whether there really is much improvement from Skylake to Kaby Lake, or is Intel just stalling while it looks for a way to stretch Moore’s Law even further.

I can say now that it’s a decent step forward. To find out just how much you get and where it’s from, you’ll have to read on.

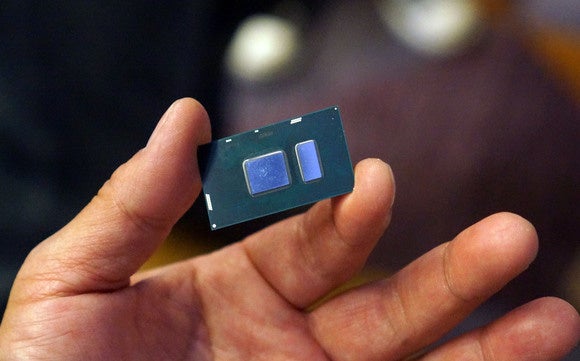

Gordon Mah Ung

How we tested

A laptop CPU is inherently more difficult to review than a desktop CPU. You can’t isolate a laptop CPU like a desktop CPU—it’s part of a complete package. Each laptop vendor makes different performance decisions for thermals, power and weight, so it can be hard to suss out the CPU’s impact unless the laptops are exactly the same. Otherwise, you’re really comparing laptop A with laptop B.

Fortunately, I had access to three generations of Dell’s excellent XPS 13. They’re not identical, of course, but they’re close enough that the comparison has some validity. I purposely selected tests that will minimize those differences.

Meet the XPS 13s

Gordon Mah Ung

The newest XPS 13 costs $1,100. It’s equipped with a 7th-gen Kaby Lake Core i5-7200U, 8GB of LPDDR/1866 in dual-channel mode; a 1920×1080, non-touch, IPS panel; and a 256GB Lite-On NVME M.2 SSD.

I reviewed its predecessor last year. It has a 6th-gen Skylake Core i5-6200U, 8GB of LPDDR3/1866, a 1920×1080, non-touch, IPS panel and a 256GB NVMe M.2 Samsung SSD.

Then there’s the original XPS 13, configured with a 5th-gen Broadwell Core i5-5200U. Because it was the entry-level model, it had 4GB of DDR3/1600RS in dual-channel mode and a 128GB M.2 SATA drive. It also had a 1920×1080, non-touch IPS panel.

Prior to testing, all three laptops were reset, and all three were updated with the same Windows 10 version (OS 1607 Build 1493.222). All three also had the latest drivers and BIOSes applied from Dell’s support site.

If your PC world tends to swing desktop, know that what we’re only looking at laptop Kaby Lake performance. Desktop CPUs (and quad-core laptop chips) are due early next year. Consider what you see here a preview of what you might see with the upcoming desktop CPUs.

Gordon Mah Ung

Three 14nm CPUs enter a bar…

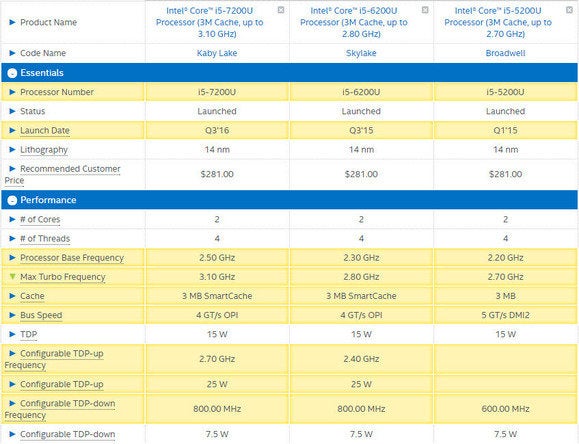

Unlike previous generations, Intel now has three CPUs built on its 14nm process. I’ve lined up the comparative details from Intel’s ARK page. I’ve also included the Core i7-6560U chip used in the gold XPS 13 that occasionally appears in my benchmark charts.

If you look at the specs below, you can find the main performance advantage Kaby Lake has—clock speed. Kaby Lake cores are, for the most part, identical to Skylake cores. By massaging the 14nm process squeeze out a CPU that can hit higher clock speeds. For example, where 6th gen Broadwell Core i5-6200U maxes out at 2.8GHz, 7th-gen Kaby Lake can hit 3.1GHz.

So what does that 10 percent increase in clock give you? Let’s find out.

Cinebench R15 multi-threaded performance

First up is Cinebench R15. This test is based on Maxon’s real-world rendering engine and is a pure CPU test. That roughly 10-percent clock speed advantage the current Core i5-7200U has over the prior Core i5-6200U results in roughly a 10 percent bump. With the older Broadwell-based Core i5-5200, the gap widens to 20 percent.

As for the gold XPS 13, you’d think its Intel Core i7-6560U and Iris 540 graphics core, with the ability to hit a maximum of 3.2GHz, would prove slightly faster than the Kaby Lake version, but it’s not. In fact, it’s slightly slower. I think the Kaby Lake Core i5 with its improved process is able to run at its highest clock speed speed for longer than the Skylake Core i7. That’s another testament to Intel’s “optimize” step.

Geekbench 4.01 performance

While Maxon’s Cinebench R15 is based on a 3D rendering engine the company sells, Geekbench is a synthetic test that tries to simulate what it believes are real-world workloads. The test isn’t without controversy, but much of that is due to Primate Lab’s attempts to make it a usable cross-platform tool that would let you compare an iPad Pro to a PC.

When you get involved in the quasi-religious wars between tech tribes, expect mudslinging. I won’t re-litigate the politics of it here, but the good news is Geekbench 4.01 is completely new, and Primate Labs seems to have taken much of the criticism to heart.

Geekbench 4.01 tests cryptography, integer, floating point and memory tests. As I didn’t have Geekbench 4.01 for the gold XPS 13, I’ve omitted that laptop. The result is an unsurprising 11 percent performance difference. Moving on to the Broadwell XPS 13, Kaby Lake shows a very respectable 24 percent improvement in performance. That pretty much echoes what I’m seeing elsewhere.

Handbrake Encoding Performance

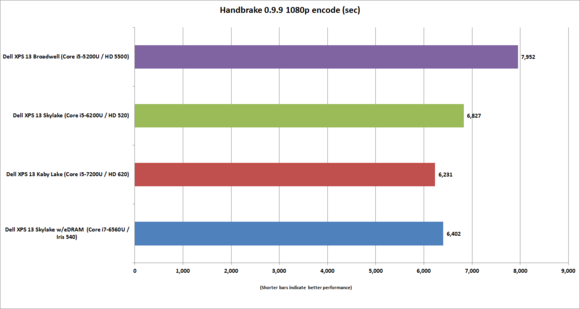

Moving on to our final CPU-centric test, we use the free and popular Handbrake encoder to transcode a 30GB 1080P MKV file using the Android Preset. The test is mostly CPU-limited and loves multiple cores.

On most ultrabooks, we use it as both a performance and thermal soak test to find out what happens to a laptop when it’s forced to heat up the the CPU for almost two hours. Typically, this is where you see the limits of the laptop’s cooling system. Performance often falls off as the it heats up—or the fans get loud. Historically, Dell’s XPS 13s have done really in this test, and that’s because Dell generally isn’t afraid to make a little noise in favor of performance.

The results for the 5th-gen Broadwell and 6th-gen Skylake are as expected, with the 7th-gen Kaby Lake coming in about 11 percent faster than 6th-gen and the 24 percent faster than 5th gen. As for the gold XPS 13 with its Skylake Core i7-6560U. Despite having a higher maximum clockspeed of 3.2GHz, the Core i7 actually finishes slightly slower than the Core i5 unit.

This seems to back up up my suspicion that the Kaby Lake Core i5, with its “optimized” process, can sit at higher clock speeds far longer than the Skylake Core i7 chip.

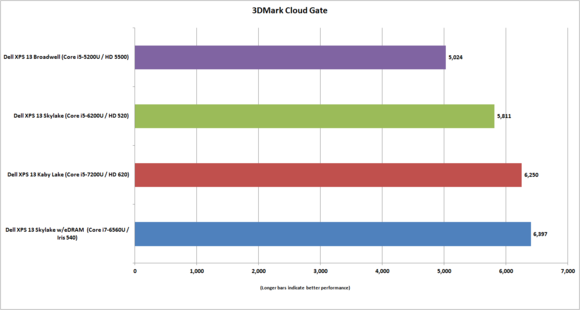

3DMark Cloud Gate Graphics performance

I didn’t get too heavy into the gaming performance of Kaby Lake, because like the CPU side, it’s very similar. The Kaby Lake chip has Intel HD 620 graphics, with 24 execution units and clock speeds of 300MHz to 1,050MHz. That probably sounds pretty similar to what you got out of Skylake’s Intel HD 520, which has 24 execution units and a clock speed range of 300MHz to 1,050MHz

To gauge the performance of the laptops, I used Futuremark’s 3DMark Cloud Gate. It’s a synthetic benchmark, but its value lies in being a neutral title that doesn’t favor any particular vendor’s optimizations. The Cloud Gate test is well suited for integrated graphics gaming, too.

In 3DMark, Kaby Lake comes in just 7 percent faster over the comparable Skylake chip. Over Broadwell’s Intel HD 5500, though, you get a very respectable 27 percent difference. Based on a 3DMark Cloud Score from the gold XPS 13 with Core i7-6560U chip. You can see where the Iris 540 graphics and its embedded 64MB of eDRAM pay real dividends.

One thing that should be said: Intel says Kaby Lake graphics can play some eSports-level games at 30 fps with resolutions and settings turned down. It’s nice that you’re getting near Iris-level performance in a standard CPU, but if games are going to be something of a focus in your laptop, get one with a discrete graphics chip (and with a Kaby Lake chip too).

Battery life is better, maybe

One of the more difficult tests in a laptop is comparing battery consumption of different CPUs. Ideally, you’d test a laptop and then swap the CPU out and test again. That world doesn’t really exist anymore, because all of Intel’s mobile CPUs are soldered to the motherboard.

The best-case scenario is what I have today. It’s not perfect but still an interesting comparison to make.

In the interest of full disclosure though, I should mention there are key some key differences. Dell uses cells that are physically the same size, but due to denser batteries has increased the capacity. The Skylake-based XPS 13 has a 57,532 watt-hour battery, while the Kaby Lake-based XPS 13 has a 59,994 watt-hour battery.

The other key difference, which may matter more, is the SSD. Both have 256GB SSD’s but the brands and rated power consumption are different. The Skylake unit has a Samsung PM951 NVMe drive which can use up to 4.5 watts, while the Kaby Lake unit has a Lite-On CX2 which absolutely sips power at 1.32 watts under load. What’s not clear is whether the Samsung drive is using a full 4.5 watts while being read from, or if that’s only a worst-case scenario. Ideally, both would have the same drive, but that’s out of my hands today. At least both pack 8GB of LPDDR3/1866.

For our rundown test, I stuck with our standard workload, which is to play the open source Tears of Steel using Windows 10 Movies and TV with the brightness set to around 255 nits. Audio was on using a pair of ear buds and the tests were conducted in airplane mode.

The result? The Kaby Lake in the 3rd-gen XPS 13 gives you an hour’s more battery life than the Skylake version. Because these are laptops I can’t separate the CPU’s role from the battery’s, but at least we’re not going backwards.

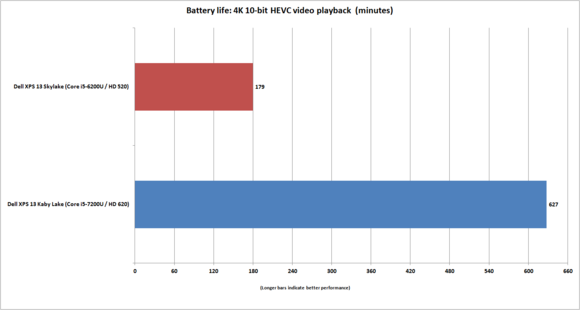

Greatly improved video engine

You know Kaby Lake’s magic on the CPU side is mostly a clock speed bump. Graphics? Another bump. The big upgrade is to the video engine, where Intel added a wealth of hardware support for such things as VP9 at 4K resolution and 10-bit color support for HEVC.

To find out the practical upshot I used an Intel-supplied 10-bit HEVC file at 4K resolution. The file was actually the same open-source Tears of Steel video, but encoded at a 10-bit color depth.

Using the same settings for the previous battery run-down test I wanted to see how much that hardware support for 10-bit HEVC mattered. As it turns out, it matters a lot.

As you can see, the Kaby Lake XPS 13’s battery life is just over 10 hours. On the Skylake XPS 13, you take a yuge hit with Skylake tapping out at just under three hours. Ouch.

Kaby Lake’s dedicated hardware for playing back 10-bit HEVC on the graphics cores means the CPU can sit idle most of the time during playback. Skylake doesn’t have the same video hardware support, so decoding of that 10-bit content is shifted to the CPU cores, which must run at at far higher speeds to process it. The more you use the CPU, the more power you use.

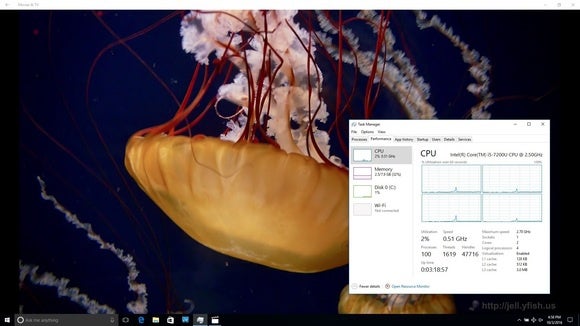

As a comparison test, I downloaded a pair of videos encoded in HEVC at 10-bit color depth from Jelly.fish.us. The files are provided so people can test network streaming performance.

I didn’t stream them though–I just played the files directly from the SSD using Movies and TV. In this first screenshot you can see the Kaby Lake XPS 13 playing the 1080p version of the 10-bit HEVC file. Because the GPU is doing all of the work, the CPU is basically idling.

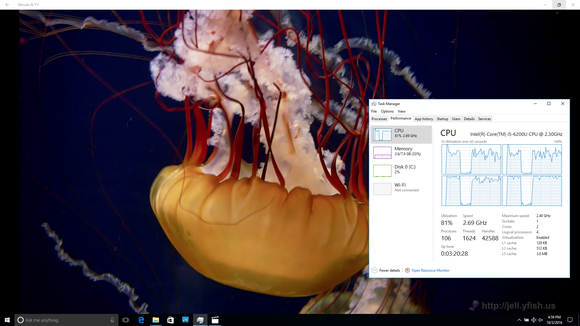

In the next screenshot, you can see the same file being played on the Skylake XPS 13 in Movies and TV. It’s pretty apparent what’s using all the power on the Skylake XPS 13: The CPU is working hard to decode that 10-bit content, and with both cores running at 2.7GHz during the playback.

What’s worse: Rhe Skylake XPS 13 constantly drops frames even with the CPU running at near top speed. To put a finer point on it: The Kaby Lake XPS 13 can play the file at 4K resolution with 10-bit color and HEVC and still cruise, while the Skylake XPS 13 can barely play the 1080p version. Ouch.

Intel says you can expect similar results for Google’s VP9 video too using the Chrome browser. VP9 is a video codec Google supports and how it encodes all videos on Youtube. I tried replicating Intel’s tests using Chrome on Youtube but didn’t have the network bandwidth at home to reliably stream two 4K VP9 videos simultaneously (one to each laptop). I see no reason to doubt Intel’s claims, though, as the claim about 10-bit content in HEVC is pretty crystal-clear.

One thing that should be pointed out: 10-bit content is very rare today. One area I think it does matter though, is in HTPC use. If I were building or buying a machine to run my 4K-and-up television, I’d want Kaby Lake over Skylake in a heartbeat.

Conclusion

In the end, Kaby Lake is a decent step forward. Is it as exciting as reading about a 10nm-based CPU? No. But it does deliver a margin of improvement that’s actually in line with the evolutionary steps that what we’ve seen from the last few generations of chips. Haswell to Broadwell gave us maybe 10 percent. Going from Broadwell to Skylake yielded similar results.

Does it mean dump your Skylake laptop and rush out to buy a Kaby Lake laptop? No, not at all. However, when you’re looking at a 20 to 25 percent difference between Kaby Lake and Broadwell, then you start to wonder. As you get to Haswell, where it probably opens up to 30 to 35 percent, or Ivy Bridge and even Sandy Bridge, then yes, an upgrade would be a game-changer.

source”cnbc”