After spending most of her life bouncing off video games, Jessica Furseth finally discovers the joy and practical benefits of play

‘Luke, how do I get this power moon? Luke!” I’m playing Super MarioOdyssey while my partner, Luke, is trying to work. “You’ll figure it out,” he says patiently. Luke has been playing video games since he was a child, but this is my first ever game, and he’s thrilled that I’m invested in Mario’s quest to save Princess Peach.

Considering it’s a $100bn (£70bn) industry, gaming is a surprisingly “love it, or just don’t get it” kind of activity. I’ve tried video games a few times over the years, as people seemed to be having so much fun with them. But I never got into it. I kept dying, so I gave up. Last year, though, my curiosity was piqued again as I watched Luke play the newest Mario game with his children. One slow Sunday, I picked up the Nintendo Switch. No one was more surprised than me when I kept coming back to the game, and eventually beat Bowser.

My newfound enjoyment of video games prompted me to want to learn more about what people love about them. A straw poll of my gaming friends revealed diverse motivations, but everyone said they found gaming relaxing and satisfying, especially after a stressful day at work. One person even said gaming had been key to recovering from severe burnout. Another told me that playing World of Warcraft with a partner helped them to stay connected while they were living in different cities.

“It’s mental weightlifting,” Luke says, when I ask what he likes about video games. There’s puzzles to solve, foes to conquer, things to collect, and maps to navigate: “It feels good to use the brain in this way.”

Video games often get a bad rep – however unjustified – for being violent, and bad for attention and literacy. But Celia Hodent, a game user-experience consultant with a doctorate in psychology, is not surprised to hear that people feel gaming adds so many positive things to their lives.

“A good game can put you into a flow state,” says Hodent – that feeling when you’re fully immersed in an activity, and time flies because you’re enjoying yourself. “When you’re watching a film or listening to the radio you may eventually check your phone. But when you play a game, you have your hands on the controller. You’re not [getting distracted]. You have to pay more attention, and you’re more immersed in the task,” says Hodent.

A large part of good game design is ensuring that poor controls or confusing levels don’t obstruct this flow state. Super Mario Odyssey’s assist mode – which lessens the penalties for failure and offers extra guidance through the game – was probably key to getting me over the hump when I couldn’t even get Mario to run in a straight line. Hodent explains how designers go to great lengths to create games that present the right level of challenge: “If the game is too easy you get bored, but if it’s too hard you get frustrated.”

“Human motivation is complicated. But self-determination theory explains that you feel more intrinsic motivation – doing stuff for the pleasure of it – when you have competence, autonomy and relatedness. And to feel competent you need to feel in control,” says Hodent.

Mario Odyssey was especially soothing when I felt tired and restless – perhaps because it was an absorbing environment where I was in control. In other words, I was enjoying playing Mario because I was getting better at it: I could get the Italian plumber to do backflips, and I could pile up a Goomba stack to get that high-hanging moon no problem. Things made their own kind of sense in the Mushroom Kingdom, and figuring out how that world worked was rewarding.

But while I have been learning, I won’t be jumping over fire rings to punch a giant turtle in the real world. Do the skills I have been gaining translate into other walks of life?

Players reported a wide range of both vague and specific ways that gaming has influenced their lives. One friend says he learned everything he knows about anatomy from the 1982 game Microsurgeon. “And weirdly, when I played Red Storm Rising, it taught me how to recognise submarines by their profiles!” he laughs. “I don’t think you have to dig particularly deep to find things about gaming that will surprise you.” Another friend bought Euro Truck Simulator to practice driving on the opposite side of the road. He also attributes his love of maps to gaming: “My older brother said I couldn’t play Nintendo, but I could be the ‘navigator’. So I would study maps. Later on, I realised that while driving, I’d have a little map in my head.”

Kenny McAlpine, an academic at Abertay University, Dundee, who specialises in gaming, says it’s certainly possible that skills built in a game can translate to real life. “We’ve always used play as a way of social interaction, education and wellbeing. As children, play is how we make sense of the world” he says.

There are many examples of how purpose-built computer games can be effective at teaching things, ranging from how kids can confront bullies to innovative thought for corporate problem-solving. Foldit is an online game that solves real scientific puzzles, for example, and Maersk has a Sims-style game that simulates the challenges around oil production in harsh environments. “Recent research projects at Abertay have applied computer game technologies to police armed-response training, cancer cell modelling and the virtualisation of historic keyboard instruments,” says McAlpine.

But when it comes to games designed for entertainment, it’s harder to tell exactly what real-world benefits they can confer. Some specific evidence has been discovered: researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden found that playing Tetris immediately after a traumatic event reduces the likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder, probably because the game interrupts memory consolidation. A study from the University of Montreal reported that playing Super Mario 64 increased hippocampal grey matter in older adults, after 3D roaming games had already been proved to do so in younger people.

“There’s a lot of hype around video games and neurosciences, and most of it is exaggerated,” says Hodent. She points to the work of the cognitive neuroscientist Daphne Bavelier as an exception: Bavelier found that playing an action game such as Call of Duty for 10 hours will improve a person’s detail vision and multitasking skills, and almost double their capacity for tracking moving objects even five months later.

But rather than focusing on a single game, Hodent says the best we can do for ourselves is to keep things fresh by playing everything from video games to Sudoku to tennis. “If you play multiple games, you’re always in a situation where you learn something new. That’s what is going to help your brain stay sharp.” The famous “nun study”, running since 1986, supports this view: puzzles seem to help keep Alzheimer’s at bay. The brain really likes a good, knotty problem.

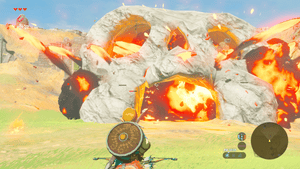

I picked up The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild over the festive holidays. I knew it would be trickier than playing Mario on assist mode, but Luke says it’s the best game he’s ever played, so I figured that it might be worth some initial frustration. I’m pretty lost with Zelda still; Link is running around in ragged trousers, and Luke refuses to help, insisting I figure it out on my own. But I know now that the further into the game I get, the better it will be – and that figuring things out and learning is what makes video games so rewarding, and ultimately, so much fun.

[“Source-theguardian”]