PosiGen Inc. was close to finalizing terms on a $100 million financing deal. Then Congress passed President Donald Trump’s tax-reform plan.

“We just lost $100 million in tax equity last week,” Thomas Neyhart, chief executive officer of the Louisiana rooftop solar installer, said in an interview. “Of course, they let us go because we’re relatively small.” He declined to identify the prospective U.S. investor.

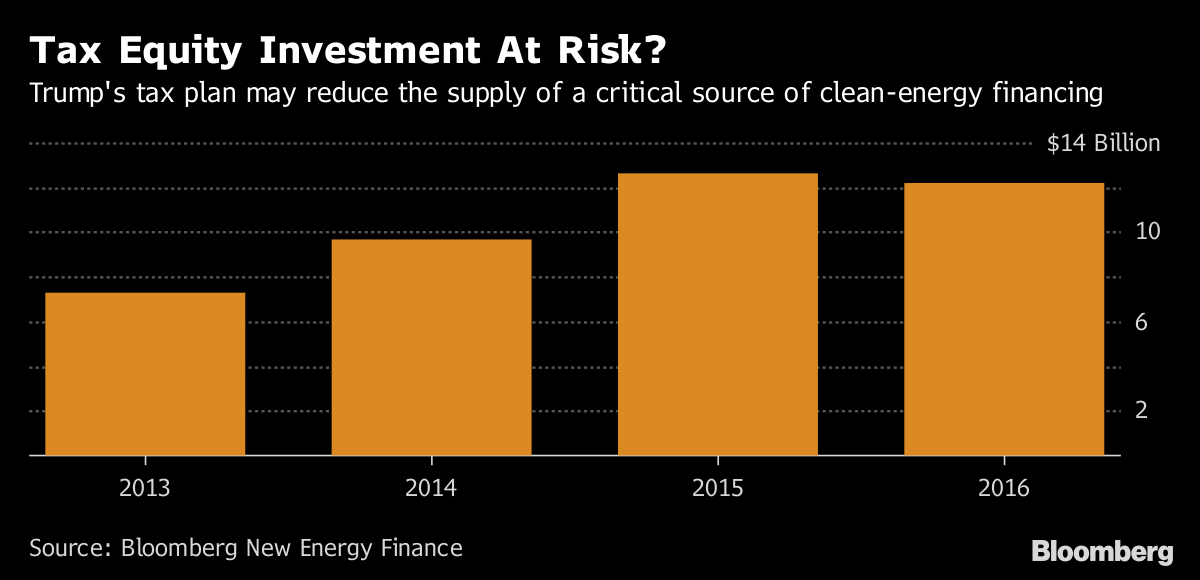

Tax equity is a critical but esoteric source of renewables financing — totaling about $12.2 billion in 2016, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. There were about 35 tax-equity investors last year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. While solar and wind projects are typically eligible for federal tax credits, many don’t owe enough to the government to take full advantage. Instead, they turn to banks, insurance companies and some big technology firms that monetize the credits through tax-equity investments.

“This adds a layer of complication,” said Jeff Waller, a New York-based principal of sustainable finance at the Rocky Mountain Institute, in an interview. “It may be a step too far for some.”

The result: a market that’s poised to “tighten,” said John Eber, a Chicago-based managing director at JPMorgan, on a webinar Thursday hosted by law firm Norton Rose Fulbright LLP. Tax-equity investors that remain in the renewables market might “moderate” their contributions, he said.

With less tax-equity investments, smaller companies like PosiGen may lose out to more established developers. For PosiGen, it means turning to a different class of investors.

“We can’t get past banks’ credit committees anymore,” Neyhart said. “We’re talking to more family offices.”

source:-.bloomberg