When users first try virtual assistants (like Siri, Google Now, Cortana, M or Alexa), they’re struck by the idea that they’re talking to a computer, rather than a person.

That much sounds obvious. In reality, however, the responses from virtual assistants are far more human than most people assume. In fact, every response is carefully crafted by a person or a team of people.

What you get as a response to your question or request to a virtual assistant isn’t what a real-live person said. It’s what a team of people believe a real-live human being could or should say.

Some replies are constructed from prerecorded words and phrases—the sentences are pieced together by software to answer some arbitrary question—and others are written as full sentences or paragraphs. Let’s take a look behind the scenes and see how this works.

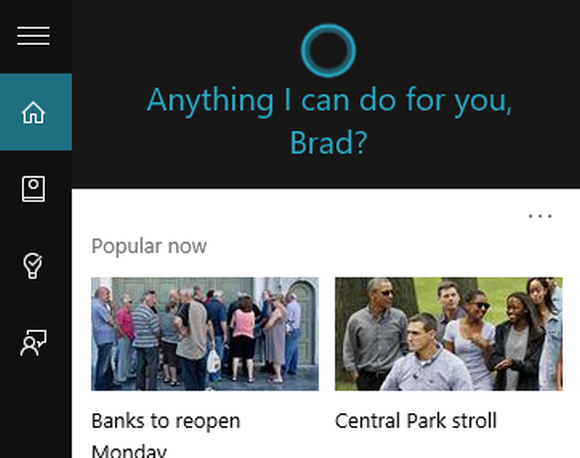

Speaking at the recent RE-WORK Virtual Assistant summit, Deborah Harrison, a writer on Microsoft’s Cortana team, revealed that in the U.S., there are eight full-time writers chugging away every day on choosing what Cortana will say. These writers are novelists, screenwriters, playwrights and essayists. According to Harrison, they start each morning with a meeting that lasts an hour or so. In that meeting, they pore over information about what people are asking or saying to Cortana, looking for problems that can be solved with better replies. (Yes: All your interactions with virtual assistants are recorded, cataloged and studied). Then the writers spend the rest of their day crafting the best responses.

In fact, the writing done for Cortana (and Siri, Alexa and other virtual assistants that have personalities) is a lot like novel writing. There’s no story or plot, but there is one character, which has a gender, an age, an educational level, a particular sense of humor and more. That human-created character or personality has to remain consistent across queries and contexts. When the writing staff crafts canned replies, it’s essentially dialogue based on the character they’ve developed.

For example, the Cortana team will take the simplest reply and agonize over whether the answer is meaningful and relatable for people from a wide variety of cultures and backgrounds and age groups. It can’t be sexist or even encourage sexism. Nor can it be militantly feminist, overtly political or even gender neutral (Cortana is not human, but she is female, according to Harrison).

Cortana even holds what some might consider religious or political views. For example, Cortana supports gay marriage.

There’s always a balance to be achieved. And having a good sense of humor is important. Cortana must be funny, but sarcastic humor is off the table.

Further reading: Ask Cortana anything: Snarky answers to 59 burning questions

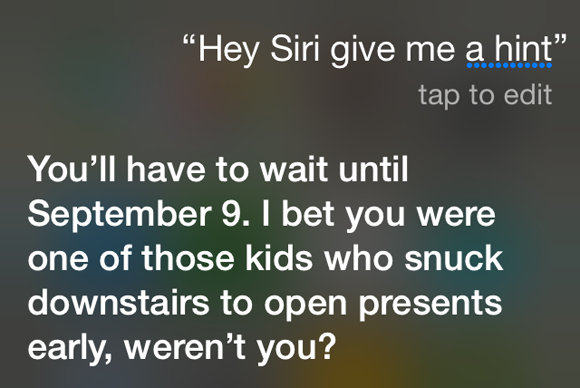

It turns out that people say all kinds of crazy, obscene and inappropriate things to virtual assistants. The people who craft answers need to decide how to deal with these questions. In the case of Cortana, the writers make a point to respond with an answer that’s neither encouraging nor funny. (By making it funny, they encourage uses to be abusive just for laughs.)

You might ask yourself: What difference does it make if users are verbally abusive to a virtual assistant? After all, no humans get their feelings hurt. No harm done, right?

Part of the craft of virtual assistant character development is to create a trusting, respectful relationship between human and assistant. In a nutshell, if the assistant takes abuse, you won’t respect it. If you don’t respect it, you won’t like it. And if you don’t like it, you won’t use it.

In other words, a virtual assistant must exhibit ethics, at some level, or else people will feel uncomfortable using it.

They also have to exhibit a human-like “multidimensional intelligence,” according to Intel’s director of intelligent digital assistance and voice, Pilar Manchon. The reason is that people form an impression of the virtual assistant within minutes and base their usage on that perception.

When we interact with a virtual agent, we’re compelled to behave in a specifically social way because we’re social animals. It’s just how we’re wired. In order for users to feel comfortable with a virtual assistant, the assistant must exhibit what Manchon describes as multidimensional intelligence, which includes social intelligence, emotional intelligence and more. Not doing so would make the agent unlikable in the same way and for the same reason that a real person without these traits is unlikable.

Those are just examples of some of the issues the virtual assistant writing teams have to grapple with. The entire process of providing responses to queries requires that a group of humans consider what the best response would be to any possible question posed by users.

Yes, virtual assistants involve monster computers with artificial intelligence crunching away on understanding the user and grabbing the right data. But the response comes in the form of words carefully crafted by people.

It’s not just a human response, it’s better than a human response. At least under the circumstances.

With real people, you can’t overcome the vagaries and perils of people having a bad day, people guessing, people lying, people expressing subtle bigotry and more.

While virtual assistant responses are far from perfect, their improvement rate is always headed in one direction—up. The people who craft these responses deal with complaints and errors and problems every day, and they chip away constantly at the rough edges. Over time, the responses get more helpful, more accurate, more carefully crafted and less offensive or off-putting, while remaining decidedly human all the while.

The database of responses becomes a kind of “best practices” for how humans, not machines or software, should respond.

How we’ll know when virtual assistants have arrived at last

Today, most users of virtual assistants are advanced and active users, and that’s a problem.

New users tend to get frustrated and stop using virtual assistants because they won’t get the right response if they don’t know how to ask the question in a way that the system understands. No virtual assistant platform is good enough to understand everything a novice says or types, and is therefore not able to provide a satisfying answer.

We will be able to say that virtual assistants have really arrived when they become the preferred user interface of novice users—in other words, when average people find virtual assistant technologies to be better, more reliable and more appealing than other computer interfaces.

We tend to focus on improvements on the machine side, and that’s super important. But the human side is always getting better, too.

Unlike other technologies, virtual assistants will become really important not when they’re fast enough or cheap enough or powerful enough, but when they’re human enough.

Because virtual assistants are people, too.

[“source -pcworld”]