A weird thing happened to me recently. I was daydreaming about hanging out with someone I’d met, someone I liked, when suddenly I had a realisation: I wasn’t just imagining us together. I was imagining how we’d look together if another person was watching footage of us on Instagram Stories.

The extent to which social media — and the exhibitionism and voyeurism upon which it depends — had embedded itself into my unconscious fantasies shocked me. But really, it shouldn’t have.

The fact is: to be a hyper-connected millennial today is to exist in multiple realities. To be both present within and outside of your own experiences, living them while simultaneously observing them; and assessing their shareability.

All of us are publishers, seeking opportunities for storytelling, producing daily content to the point that we’re almost convinced that our Instagram feeds are a truer representation of ourselves than who we are IRL. We’ve bulldozed the walls between public and private, edited out the messiness, embraced a self-regarding gaze of constant surveillance.

How many likes will this get? Am I funny enough? Hot enough?

Does this look too edited? Or too real?

Every Instagram post is a case study on how much people “like” us. And while millennials joke about our personal brands — the neat, saleable versions of ourselves, the digital shopfronts advertising our own personal USPs — they are ultimately how we communicate to the world and, increasingly, how we make sense of our own identities to ourselves.

Mine can be summed up like this: lots of black, slicked hair, Margiela Tabi boots, a Prada backpack, lurid 1970s horror films, Cindy Sherman. Give me a series of things and I’ll tell you instantly whether they’re on brand for me. Kathy Acker = yes, Charles Bukowski = no. Sphynx cats = yes, spaniels = no.

Despite my Tabi boots and Prada backpack, I am not a brand. I am a person.

My professional life as digital head of fashion for Dazed offers up countless opportunities to project a glamorous image to my followers: runway shows, freebies, celebrity encounters. Part of my day-to-day role is also the management of a successful Instagram page, so I understand how it all works.

I know that cultivating a personal audience of highly engaged fans would be a good career move, whether in terms of building a bigger client base for my freelance work or embarking on a long-term plan to leverage the perks of my job into content, quitting when I’ve got enough followers to start charging $10k a post. This, the current culture tells us, is what success looks like.

But the pressure to keep up appearances that comes from comparing myself to the cultivated personas and consistent aesthetics I see every time I unlock my phone — especially from people within the industry, where we all know appearances matter — is draining. And it’s not just me who is feeling the strain.

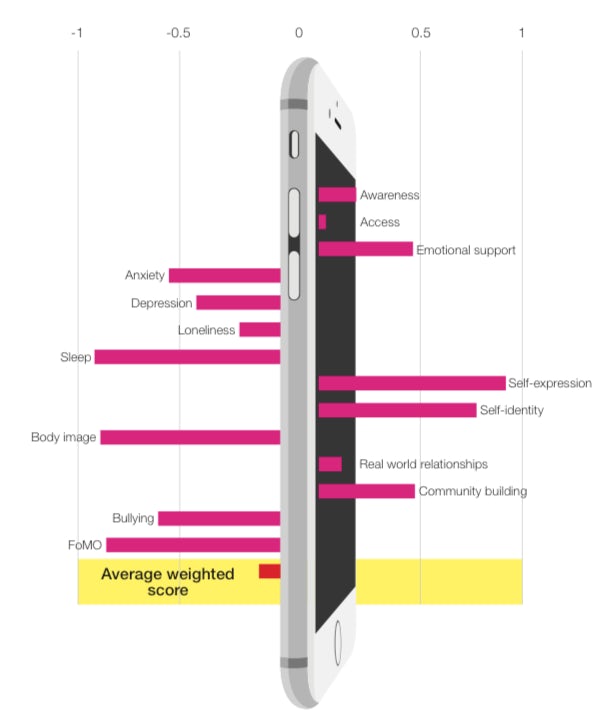

A 2017 survey by the UK’s Royal Society for Public Health on the effects of social media on British youth linked use of these platforms to anxiety, depression, lack of sleep, worries about body image and “FOMO” or fear of missing out, with Instagram being the most damaging platform, especially amongst women.

Source: Royal Society for Public Health

Carmen Papaluca, a PhD researcher at Australia’s University of Notre Dame, recently discussed her findings from surveying 18- to 25-year-old female Instagram users with Dazed. “It’s really gone past just wanting to look like somebody,” she explained. “Now it’s about having their life.”

This, Papaluca’s research says, is especially true for women in their mid-twenties rather than teens and those in their early twenties (who mostly feel badly about their bodies). And as much as I’m terrified to shatter the veneer of complete confidence we’ve been told is necessary for a successful career in the fashion industry and admit this, I know the feeling.

A few weeks ago, I was on an incredible press trip to Shanghai with a luxury house. Despite the privilege of my situation, ten seconds of scrolling down Instagram was enough for me to feel unsatisfied about my own life compared to the ones I saw others living — or at least performing.

Last week, I posted an Instagram story about my complicated relationship with social media. The responses were many and a theme emerged: we are exhausted. We’ve edited out the parts of ourselves that didn’t fit, willingly become hollow strings of keywords ripe for data mining, handed over our emotions to an algorithm which understands us better than we do.

We thought we’d found a solution in the creation of “finstas” or fake-Instas, private accounts with obscure usernames and limited followers where we felt we could actually express ourselves — but even they began to feel like another character we had to play. We’ve started to wonder: where do our personal brands end and our actual personalities begin? Who would we be, if we ever let our phones go dead?

We’ve started to wonder: where do our personal brands end and our actual personalities begin?

It’s pretty easy to figure out why The Matrix has been one of 2018’s biggest fashion inspirations, and why Lil Miquela — the computer-generated Instagram it-girl — has been the most talked about influencer we’ve had in years. Because, as hunky social phenomenon Jay Alvarrez’s bio declares to his 6 million Instagram followers, we’re all “lost in the simulation.”

It’s Guy Debord’s “Society of the Spectacle” on crack.

In a trend report released last December, forecasters Box1824 (who, working with K-Hole, were responsible for the term “normcore”) break down millennial anxieties and predict that things will be different for the next generation, those born after 1998, which they call GenExit rather than Gen-Z.

“GenExit knows maintaining a Personal Brand is a trap,” the report says, noting the younger group’s preference for the perpetually ephemeral nature of Snapchat over a curated Instagram feed. “They don’t want to invest scarce emotional resources into marketing themselves.” Rather, freedom and fluidity are key.

So, maybe there’s still hope. For brands redirecting large parts of their marketing budgets towards sponsored Instagram posts, this probably isn’t what you want to hear. And none of this is to say that Box1824’s predictions will turn out to be true, that my neuroticism is universally shared or that social media can’t be used in moderation or as a force for good.

Similarly, personal brands, especially in fashion, were certainly not an invention of the internet; the internet has just allowed for their constant, data-driven performance tracking.

This is not an attack on those who have made being an influencer a full-time, highly profitable career. I’m also not saying we should all get flip phones or live in the wilderness. But for my fellow highly strung, self-aware millennials, scrolling anxiously through the sea of impressive illusions we’ve each worked so hard to create… something’s gotta give.

If social media is more a source of stress in our lives than of community, education, entertainment or anything else positive, it’s time to rethink the almost totalitarian power over our identities and emotions that we have willingly ceded it.

I don’t know about you, but I can’t go on like this. Despite my Tabi boots and Prada backpack, I am not a brand. I am a person.

After willingly shackling myself up in Plato’s cave watching Instagram Stories instead of the shadows on the wall, I need to find my way back into the light.

source:-businessoffashion