A farmer using a mobile phone while resting in the back of a tractor trolley on a blocked highway during a protest against new farm laws, at Singhu Border (Delhi-Haryana) in New Delhi, India.

Image by Raj K Raj/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

On January 26, Nidhi Suresh of Newslaundry travelled with farmers from the Singhu border to Red Fort but could not send any information back to her newsroom.

The same day, Asmita Nandy of The Quint could not look up the speeches that protestors at the Singhu border kept referring to.

On January 27, independent journalist Saahil Murli Menghani tweeted that he could not upload videos from the Republic Day tractor rally on Republic Day itself.

On January 29, a group of people at the Singhu border pelted stones at protestors. Himanshi Dahiya of The Quint, who was present at the site, could not relay the information back to her editors. Neither could Menghani post a live video.

On January 30, Menghani tweeted, “Unable to put reports as 2G speed internet here at Tikri. No worries. Uploading of reports will NOT stop. Even if that demands walking a few KMs. Won’t let this attempt to hinder ground reportage succeed.”

On February 1, independent journalist Sandeep Singh saw trenches being dug up at the Singhu border, barricades being erected but could not tweet about it to his 29.6 thousand followers.

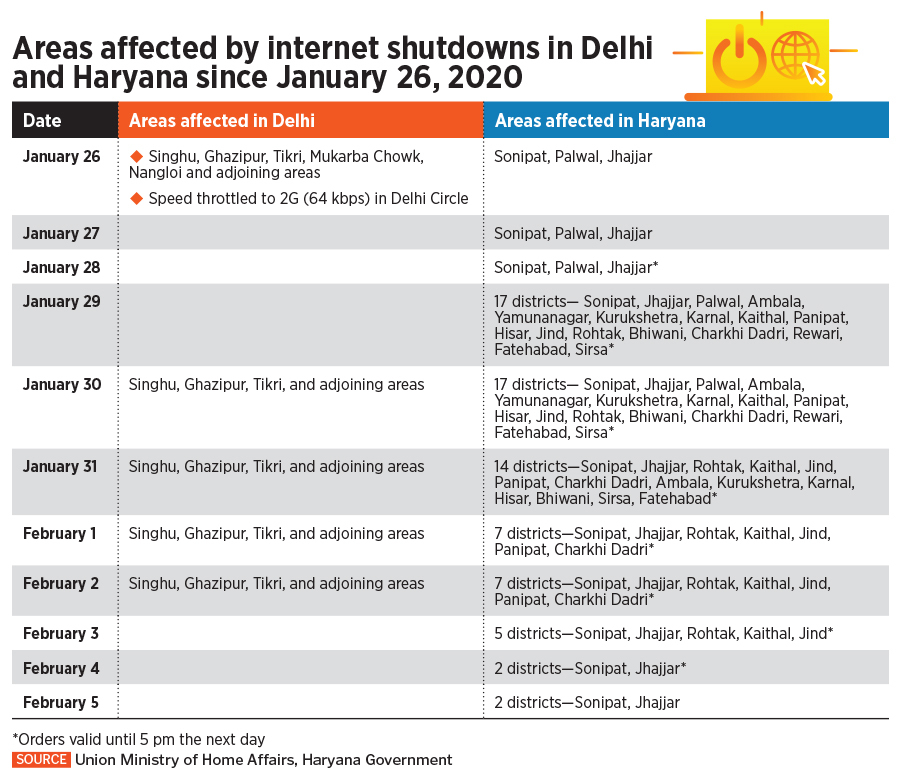

Since January 26, mobile internet services have been intermittently suspended in most of Haryana and at the Delhi borders. In Delhi, that meant complete shutdown of mobile internet services in the border areas, and in Haryana, that meant no bulk SMSes in addition to a suspension of mobile internet. The aim, at least as stated by the Haryana government, is “to stop the spread of disinformation and rumours through various social media platforms, such as WhatsApp, Facebook Twitter, etc. on mobile phones and SMS, for facilitation and mobilisation of mobs of agitators and demonstrators who can cause serious loss of life and damage to public and private properties by indulging in arson or vandalism and other types of violent activities”.

But the step has meant that not only have protestors been cut off from access to information but journalists reporting from the sites too have been cut off from their newsrooms, making it difficult for them to look for information, verify facts, gather context or relay information.

For many of the journalists Forbes India spoke to, the situation was not unprecedented. They all remembered how mobile internet services had been suspended in the heart of the capital in December 2019 during the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act.

Communication with newsrooms, fact-checking becomes difficult

While reporting from the ground, journalists often verify facts online before relaying information back to the newsroom. “At the Singhu border itself, a lot of people told me about speeches that were uploaded the previous night, on Monday [January 25] night. I wanted to check on these things on the ground [to gain context about the situation], but even that was an issue,” Nandy, who has reported from Singhu and Ghazipur, says.

For instance, when freelance journalist Mandeep Punia was detained on the night of January 30 at the Singhu border, Suresh and her cameraperson were at Singhu border but at a different spot. They heard rumours that another journalist, Dharmender Singh, had been detained. “We had no idea who they were. We couldn’t look up anything, and it was completely chaotic,” she says. Singh, a journalist with Online News India, was ultimately let go while Punia was granted bail on February 2 by a Rohini court.

Publications like The Quint are dependent on videos which require a fair amount of internet bandwidth. But with internet shutdowns, even relaying basic information became almost impossible, Nandy says. At The Quint, reporters often send a few lines of new information from the field and the rest of story is then written by colleagues in the newsroom. However, without new updates, even that became impossible.

Relaying of video footage is delayed until journalists exit the protest site. Nandy recalls that footage recorded at 2 pm in the afternoon at the Singhu site could only be sent back to the newsroom at 6 pm, when she came out of the protest site. “And then the processing [editing into a package] gets started and ultimately the video could only go out the next day,” she says.

The geographical spread of the protest sites means journalists have to at times walk 2-3 kilometres to exit the protest sites and access the internet to relay footage, and then walk back in for fresh footage and reporting. And if the newsrooms need more context, that communication too gets delayed. The Tikri protest site, for instance, stretches to almost 15-16 kilometres, says Dahiya. While the Singhu protest site, says Suresh, “easily spans about 8-10 kilometres”, adding that barricading starts a kilometre to a kilometre-and-a-half before the protests begin.

This size also means that if something happens in one area of the protest, and a reporter is five kilometres away but still within the protest site, they do not have any means of knowing what is going on.

Newslaundry has a workaround—a person sits in the newsroom, with access to internet, and monitors social media and other news reports. In case something happens, they call Suresh and tell her to proceed to another part of the protest site. But lags, are, of course, unavoidable. “It obviously slows down your work, it slows down information dissemination,” she says. But there are not many options available. “That’s the best we can do to get the news out.”

It also becomes difficult for journalists to coordinate with their colleagues within the protest sites. What Dahiya calls “intra-protest communication”, which journalists also rely on to reach incident sites, had been completely decimated. “Crucial information pertaining to a particular point of occurrence gets lost,” a journalist who has been reporting from the three protest sites for a national English daily since November 2020 told Forbes India. Journalists rely on WhatsApp and Telegram groups to share such information. They also rely on live images from reporters on the ground. Incidentally, our WhatsApp call with the print journalist got disrupted since he was approaching one of the border areas.

NDTV’s Chandigarh-based Mohammad Ghazali relies on a network of local reporters spread across Punjab and Haryana for ground reports. When Forbes India spoke to him, he was reporting on the Mahapanchayat in Kurukshetra. Local reporters who send him reports from Singhu or Tikri first have to travel into Delhi, either on foot or via car, to get network connection or to scramble for Wi-Fi. Public transportation is not an option because it is not available in a number of areas close to the protest sites.

Independent journalists, freelancers bear the brunt of shutdowns

Though the shutdowns affect all journalists, independent journalists like Menghani, Singh and Bali who rely on social media to get news out, are particularly affected. Menghani, for instance, regularly uploads videos to Twitter, YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Singh and Baali have been regularly tweeting photos from protest sites. Live and verified updates are what bring people to their social media handles.

For Menghani, who has a decade of experience in broadcast journalism and is known for his #Verified series of stories on digital platforms, the loss of live reportage means he cannot stream “non-choreographed” images and videos which capture the moment as it is. For instance, he shot a 41-minute long video of 2,000 farmers running from Rohtak-Sample to bring 2,000 flags to Ghazipur that he could not go live with it. “Imagine a live, uncensored, uncut video of me atop a tractor going at 30-50 km/hour, recording farmers running to the capital with Indian flags. It would have driven home the urgency of the situation.” It has taken away the live element of ground reportage,” says Menghani, who has 82.5 thousand followers.

Due to throttled speeds, he could not even calculate how much time it would take him to commute from one spot to another.

Singh, who has written for The Wire, The Quint and Gaon Connection in the past, has been following the protestors in person since November. “Most of my followers follow me for live tweets. I rarely do longer stories. They follow me for breaking news,” he tells Forbes India. He has been relying on WiFi from local shops, whenever he can get it but in the interim, he calls up a friend who has access to his Twitter account and asks him to tweet on his behalf. “All the tweets which say ‘Twitter for Android’ are the ones I told him [the friend] to tweet. I cannot even check if he has tweeted them,” he says. Sharing any photos or videos is completely out of the question.

While media houses have ample resources and staff, freelancers are on their own. “In case one reporter is tired, they [a big media house] can send someone else,” Suresh says.

Bali, for instance, who also has a contract with HarperCollins for a book on 100 years of agrarian unrest in India and has been following the farmers’ protests since June, often ends up sleeping in his car. On Republic Day, after the imposition of the internet shutdown, he followed the protestors back to Singhu border where the protest site was rife with rumours since nobody could verify whether everyone had come back. “As a result, the protestors came up with a temporary solution—a “trolley to trolley survey” where they should look out only for their trolley mates with whom they shared the trolley at night,” he recalls.

But the shutdowns affect everyone. Even print publications have digital arms that rely on live and continuous updates, the print journalist quoted earlier says.

Broadcast journalists too have their set of challenges. Increasingly, broadcast journalists have been relying on mobile journalism, colloquially called “mojo”, but that is also out of the question during an internet shutdown, Akshay Dongare of NDTV says. Reliance on outside broadcasting vans (OB) vans, which are capable of transmitting footage without internet, is also not an option as they are parked outside the protest sites.

Affecting daily life

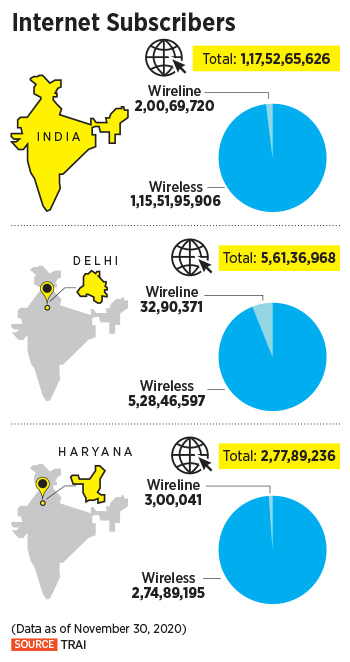

According to data from the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), 98.3 percent of the Indian population that is connected to the internet relies on mobile internet services and dongles. In Haryana, the percentage increases to 99 percent of the 2.7 crore total subscriptions. In Delhi, on the other hand, of the 5.6 crore internet subscription, 96 percent are mobile/dongle subscriptions. As a result, shutting down mobile internet services affects at least 95 percent of the population in that area, if not more. That also includes students who are relying on internet for online classes amidst the pandemic and patients who rely on e-consultations.

Normalised for population and assuming that people with internet use it for two hours a day, Prateek Waghre, a research analyst at think-tank Takshashila Institution estimates that the shutdowns have impacted more than 108 million hours of internet connectivity in Haryana.

Community networks of solidarity emerge

On January 31, using the crawling speeds of 2G, Menghani tweeted at 8:40 pm: “HELP- Need WiFi in SAMPLA🙏”. Within a few minutes, he had received a direct message from a stranger in Rohtak, offering the services of his friend who lived in Sampla, a tehsil in Rohtak. However, that friend was away in Bangalore so he connected Menghani to another friend in the area. Menghani went to their house where they not only offered their WiFi but also offered to let him stay the night.

This was Menghani’s first visit to Sampla but without access to MakeMyTrip or Google, he could not even figure out the hotels in the area. “I needed a place with credible speed so that I could upload the video to YouTube and tweet out the link,” he says.

Other networks have also emerged. Kisan Ekta Morcha and other volunteers from the Sikh community who are also IT professionals are identifying places where Wi-Fi hotspots are available in Tikri and sharing those with journalists, Menghani says. His Twitter messages often contain messages from people offering locations of other places with WiFi. These are not just commercial establishments, but also people’s residences.

Bali describes how a number of hotels at Tikri border, a number of Oyo Hotels in the Kundli region near the Singhu border started offering free Wi-Fi services on January 27 itself. At Tikri, a dhabha owner had posted the Wi-Fi password outside for people to use.

However, these altruistic measures also have their limits. Most of these sites are a few kilometres away from the main protest sites. The modems for these wired connections are not meant to support more than a few people. When hundreds of people connect to them simultaneously, it causes the speed to lower to unusable extents, Dongare says.

To mitigate the problem of no internet, one such endeavour is ‘Wi-FiLangar’ at some of the protest sites. Harteerath Singh, a community development director at Hemkunt Foundation, in his individual capacity, has been trying to set up Wi-Fi connections at hotels and dhabas close to the protest sites since January 30.

“We saw a drop in the number of journalists coming to Singhu because they could not report live from here. That’s the main reason we installed the Wi-Fi so that people could see the ground reality,” Singh, who visits different protest sites at the Delhi border, told Forbes India. “There are a lot of rumours out there which are not even closely related to what’s happening in reality,” he says. When we spoke on WhatsApp, he had driven a few kilometres away from the Singhu border protest site to get network.

Access to the internet also helps the elderly protestors connect with their children. A 70-year-old Delhi-based woman, who requested anonymity, has been attending protests on her own for almost a month. Once the internet services were suspended, she could no longer connect with her children. “They were very worried. I had no contact with anybody at all,” she says. Once the Wi-Fi was set up and volunteers helped her connect her phone to it, she has been regularly talking to her children on WhatsApp. And she is not the only one. There are a number of women of her age at the protest site and she points out, “We are very secure.”

To install the routers, the volunteers approach the local hotels and dhabas. “We choose locations that have landlines. Most of the locations where the Wi-Fi is now available, dhabas and hotels. We use their compounds, or at a petrol pump,” he says. Owners at times agree, and at times do not. “We pay them a rent sort of a thing on a daily basis. Obviously, if there are so many people lined up outside their hotel or restaurant, they will be a bit irritated,” he says.

A number of dhabas and hotels want to remain anonymous so Singh does not tweet about them but spreads word on the ground.

“Internet shutdowns do not help curb misinformation”—all the journalists Forbes India spoke to were unanimous in their assessment. “Fact-checking is greatly disrupted by internet shutdowns,” Raman Jit Singh Chima, Asia Pacific Policy Director at Access Now, the organisation behind the Keep It On campaign against internet shutdowns, says.

“Timeliness of things is most important. You can’t give live updates, your work is doubled, the signal is low,” says Suresh. “It limits the communication within the protests and limits what the media can relay outside,” adds Dahiya.

The absence of access to verified information could also cause rumours to easily gain critical mass. “On Friday, when I was there, there was a lot of anxiety. I could feel the anxiety within the protestors because they had no information about what was happening in the outside world,” says Dahiya. If rumours start, there is no way for protestors to verify them. While it is true they could make a normal call to a person to verify information, Dahiya points out that not everyone has the contacts to do that.

For instance, on the night of January 28, there were rumours that the police had started swinging lathis and had brought water cannons to the Ghazipur border. However, since mobile internet services had not been cut off, Menghani could put out a tweet with a video dispelling the rumours. “In the absence of internet, at most I would have put out a textual tweet which would not have had the same impact,” he said.

Chima, who is also chairperson of the board of Internet Freedom Foundation, agrees. “It doesn’t work very well because what happens is that you cut down internet access while certain channels of easy spread of messages may be switched off, people still have access to what they have received earlier and they are unable to receive updates or fact-checking information about what is correct and what’s not correct,” he says.

Menghani calls it a Catch-22 situation. “While it curbs misinformation, it also stems good information,” he points out. It obstructs the flow of information. “For instance, I could not even report about a march that was happening from Rohtak to Ghazipur,” he says.

Forbes India reached out to the Haryana Government’s Home Department for comment a number of times via phone and email, but did not get a response.

As far as “mobilisation of agitators” is concerned, Menghani points out that internet penetration is not very high which means there is low dependence on the internet. Communication is still happening via village heads, landlines or normal phone calls so mobilisation is still happening.

However, internet is still the primary source for information in Haryana. And not just via Google. There are a number of local news channels that run entirely on Facebook. When the internet was working, farmers were going live on Facebook and Instagram showing what was going on the ground, says Singh.

While people in Delhi or Mumbai may be more dependent on “national media”, Menghani says, people in Haryana are more dependent on Karnal Breaking News, which is followed by more than 19 lakh people on Facebook. Due to internet shutdowns, not only are national media organisations handicapped, but so are these local news channels that are entirely dependent on the internet.