Ninety frames per second. That’s the new target for consumer VR gear: you need hardware capable of rendering two HD images with all the trimmings at a steady 90fps, or the whole thing starts to shake and judder and make you sick. That 90fps requirement is what’s driving the disturbingly high VR system requirements posted a few days ago for Elite: Dangerous by Frontier Developments; according to Frontier, you need 16GB of RAM, a fast i7 quad-core CPU, and a GeForce GTX 980 to do VR well with Elite and consumer VR hardware.

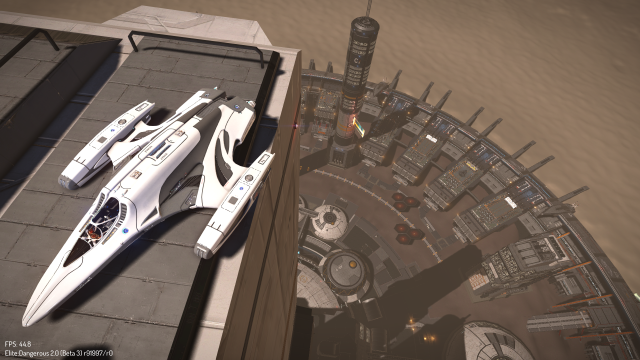

Studio founder and CEO David Braben is aware that the spec is high—the recommended video card alone will set you back at least $500—but Braben is in somewhat of a privileged position among game developers: he has one of the only shipping triple-A games that, as of today, officially supports VR without having to dig into config files and enable hidden dev-only options (I’m looking at you,Alien: Isolation). The game’s soon-to-be-released “Horizons” 2.0 expansion, which is currently in semi-open testing by the Elite playerbase, raises the bar and adds SteamVR support alongside Oculus Rift support, meaning you could plug an HTC Vive into your computer and play Elite: Dangerous on it right now, at the 90 frames per second the Vive prefers for glass-smooth head tracking.

Elite is one of the best VR experiences a PC gamer can have right now—and believe me, if a PC game supports VR, I’ve tried it out on my Oculus Rift DK2 at home, which is attached to a gaming PC that meets or exceeds Frontier’s VR spec in every category (I have a 980ti video card, but only one—SLI in Elite with VR is currently problematic due to a combination of different issues). Braben explained that the game’s VR support is the result of a complex dance of intuition and design iteration.

“It’s as much because we are gamers as well as developers that we really wanted—particularly people on the team—wanted us to support VR,” he said. The game’s UI was laid out in the early design process in such a way that head mounted displays would integrate seamlessly into the intended interactions—like looking left and right to summon up additional interface panels–and after a short amount of development, VR support was added into the alpha. It worked surprisingly well from the outset—something that Braben attributes to the way Elite closely matches the player’s in-game avatar with the player’s real-life body—seated, grasping controls, and with the primary means of “interacting” with the environment being limited to moving one’s head around.

“There’s some very valuable learning that we’ve got from it,” said Braben of launching VR support in the game’s alpha, which happened even before the Oculus Rift DK2 became available. “What makes people feel sick, what is a really good experience, what is natural, where should you put the focus distance for people—all of those things make a difference to how nice it feels.” Braben also said that the fact that Elite: Dangerous uses Frontier’s in-house Cobra engine instead of licensed technology has made it easy to create a feedback loop to iteratively improve VR support with each game update. Braben says, for example, that the optimization work that went into the Xbox One port of the game was used to improve and speed up VR.

De-sicking the experience

Having steady visual referents like a cockpit and instrument panel is an important part of “comforting” the player’s vestibular system, but Braben said that the team has found a number of other important things that apply to solid VR design—like eliminating fast point-of-view shifts or jolts. De-coupling the seated experience of the player in real life from the player’s in-game avatar seems to be the quickest way toward nausea.

“The fact that you’re seated on a sofa or whatever in a desk chair, and you’re seated in-game,” he said, is what makes it work. “It’s when the thing starts bouncing around and things like that where it doesn’t match that you start to get the warning signs,” he said. He went on to describe his experience with the Sony Morpheus demo “The Deep,” where you experience a Great White attack while in a shark cage underwater, and said that his particular run-through ended with the shark delivering an enormous wallop to the cage, which rocked his entire visual field. The huge, sudden visual perspective jump—which wasn’t matched by anything his standing body was experiencing—made his stomach lurch.

“It’s that sort of disconnect—the sudden massive movement of your virtual character that you don’t sense, I think that, I would personally say, is a bit of a no-no,” he elaborated. “And so we have been very careful, so that with Elite: Dangerous, for example, we found shaking the cockpit’s all right, but any sudden, large displacement will make you feel nauseous.”

“This is where, I think, 90 frames make a big difference,” he said, referring to the step up in the consumer versions of the HTC Vive and Oculus Rift to 90 frames per second. “The lag factor, so that when you start the movement, when that’s reflected in your vision—that time delay is another thing that can be key. All of this is about making the experience as good as possible.”

The kind of accommodations necessary for a solid VR experience cannot be bolted on, continued Braben. “You’ve got to have it in mind,” he continued, speaking about the integration of VR into a game. The parts Braben called “the hard bits” are applicable no matter what VR headset or SDK is being targeted by a developer. “The hard bits are getting your content right, getting your frame rate optimized so that you can get 90 or close to, is really important—that is a big step above seventy-five,” he said, referring to the 75 FPS refresh rate used by the Oculus Rift DK2.

That 90 FPS requirement makes everything a lot more complex, requiring developers to make timing decisions in how quickly the game’s physics and logic update themselves.

“It takes everything to the edge a bit more—making sure that your game loop isn’t running at a lower speed,” he said. “Because where you might not notice it on a bigger flat screen, it’s much more apparent on a head-mounted display, because when you move your head around, you can see things like if the physics isn’t updating at the same speed. And we did play around with that, because it does increase the load on the machine.”

That’s no moon—wait, yes it is

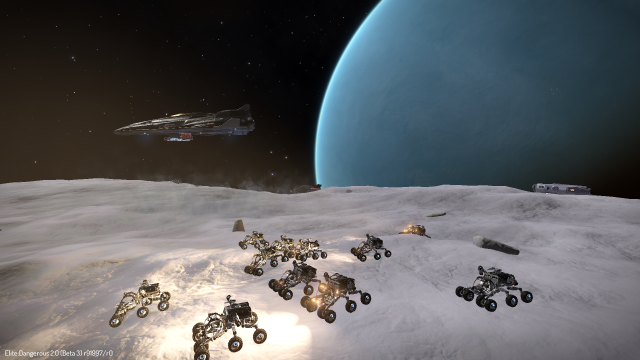

Though there were major under-the-hood changes for the 2.0 “Horizons” expansion, like the addition of SteamVR support, the most visible addition is planetary landings—a feature that many long-timeElite fans have been clamoring for since the game’s crowdfunding phase. Horizons finally brings players the ability to land on moons and planets, though at least for now it’s restricted to moons and planets without atmospheres. The expansion also adds a surface rover (called an “SRV,” for “surface recon vehicle”) that players can drive around on surfaces and a whole set of new planetary-focused missions. There will also be a loot and crafting system (the basics of it are there in Horizons now, but it will be greatly expanded on at some point after Horizons leaves beta).

All this ratchets up the graphics requirements, and Braben admits that the rendering load on the game’s engine is much, much higher now than it was before Horizons. VR, of course, makes things even more complex.

“We’ve actually got a much heavier rendering requirement now with planetary surfaces, especially when you’re near a lot of ships or your base,” he explained. “We put in these things that are interesting, and players will tend to congregate! I’ve already seen ten-plus ships and sixteen SRVs, all bouncing into each other. And it’s those things, together with all the planets and shadows, that tend to load.”

Overall, Frontier is pleased with how the Horizons beta is going—as the “2.0” version of the game, it represents the path forward for how Elite is going to be developed. Airless planetary landings will be augmented by looting and crafting, which will expand on the very basic system in place right now and will allow players to gather resources from various places and build and repair ship components with them. At some point, this will be joined by the “multicrew” expansion that will let players populate the spare seats in their cockpits with other players; also on the list are small ship-launched fighter craft, which could potentially be controlled by those other players. Further down the line will be features like a first-person mode, allowing players to walk around their ships; Frontier will also eventually expand planetary landings so that they can be done on objects with atmospheres.

Virtual reality choices

The best guess anyone has right now about general availability for the consumer versions of both theHTC Vive and the Oculus Rift is “Q1 2016,” and the big question I have—and one that I think any VR-minded player will have—is which headset to choose. Building on the old photographer’s adage that the best camera is the one you have with you, the likeliest answer to the question of which VR headset is best is whichever one you can find in stock. Still, we asked Braben if Frontier had any plans to favor one particular headset—or VR SDK—over another. His answer was refreshing.

“I would hope,” he said, “that the game will support as many head-mounted displays as we can and that internally within our engine it’s all the same pathway. The Oculus SDK continues to be in flux as Oculus pushes toward their own 1.0 release, but Braben noted that with some fiddling, the Rift DK2 works today under SteamVR, which of course also supports the HTC Vive.

Frontier’s official stance is that at launch, the Rift and the Vive will be “pretty close” in terms of the experience they deliver to players. There are some differences in the hardware, but Braben was enthusiastic about both—again reinforcing that the “best” choice initially will probably be whichever one you can buy first (crazies like me will probably buy both).

From the perspective of experiences to be delivered, Braben is most excited about freeing the player from the shackles of the cockpit chair—though that obviously brings with it a whole additional set of challenges in VR, including giving up the proprioceptive “safety net” of keeping the player seated. Indeed, today in Elite, nothing stops a VR-equipped player from simply standing up in real life—though the in-game avatar doesn’t get up with you, your viewpoint perfectly tracks, and you can walk freely around the spacecraft’s cockpit (up to the limits of your VR headset’s cable bundle and tracking camera, at least).

“We’ve got to have a lot of things to back that up,” he said, referring to the seemingly simple process of allowing a player to stand up. It already looks good, but getting it to feel good is key—and we look forward to trying, with whichever headset we end up getting first.

[“source-arstechnica”]